The Mortuary Temple of Ramses IIIRamses III ruled Egypt for some thirty years during the 20th Dynasty, when central power was weakening, foreign influence was declining and internal security was poor. In fact, he was the last Ramses of any consequence. After his death the state priesthood of Amon acquired increasing power and finally seized the throne and overthrew the Dynasty.

![]() |

| Temple of Ramses III |

Ramses III had successful battles in Asia and in Nubia. His most important battle was against the ‘People of the Sea’ who attacked Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. This battle, and his wars in neighbouring lands, were recorded in his temple. It was built on the same plan as the Ramesseum of Ramses II, but is unique in having been contracted and decorated progressively, as the campaigns of Ramses III occurred. It therefore provides a step-by-step record of his military career, and has the added advantage of being extremely well preserved.

The First Pylon is covered on both sides with representations and inscriptions of Ramses Ill’s military triumphs. On both towers there are grooves for flag-staffs, and the pharaoh is dcpicted in the traditional pose of dangling enemies by the hair while he smites them with his club. On the northern tower (a) he wears the Red Crown and stands before Ra-Harakhte. On the southern tower he wears the White Crown and smites the captives before Amon-Ra. Both gods lead forward groups of captives. The captured lands are shown as circular forts inscribed with the names of the cities and surmounted by bound captives.

At the foot of the pylons the scenes show Amon seated, with Ptah standing behind him, inscribing the pharaoh’s name on a palm leaf; the pharaoh kneeling before Amon and receiving the hieroglyph for ‘Jubilee of the Reign’ suspended on a palm-branch, and Thoth writing the king’s name on the leaves of the tree.

The First Court (A) had a colonnade with calyx capitals to the left, and Osirid figures to the right; the latter were badly ruined by the early Christians. There is an interesting representation on the inner side of the first pylon (b). This is the Libyan campaign in which mercenaries took part. They are recognisable by the round helmets on their heads, ornamented with horns. The pharaoh, in his chariot, charges the enemy and overthrows them. The scenes on the side walls repeat the victorious war themes, and the triumphant return of the king with his captives to attend the great Feast of Amon.

To the rear of the court, at (c), Ramses leads three rows of prisoners to Amon and Mut. They wear caps adorned with feathers and aprons decorated with tassles. At (d) there is a long series of inscriptions recording Ramses’ military triumph over the ‘Great League of Sea Peoples’.

![]() |

| Temple of Ramses III |

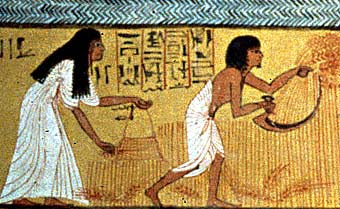

An inclined plane leads us through the granite gateway of the Second Pylon and into the Second Court (B), which was later converted into a church. Due to covering the ‘heathen’ representations with clay, the reliefs have been preserved in good condition. On both sides of the court are marvellous processional scenes. Those on the right represent the Great Festival of the God Min, and those to the left, the Festival Ptah-Sokaris. The scenes in honour of Min, like those of the Ramesseum, show trumpeters, drummers and castanet-players. In one scene the pharaoh is borne on a richly- decorated carrying chair with a canopy (e). He is led by priests and soldiers, and followed by his courtiers. He sacrifices to Min (f) and, in the sacred procession, marches behind the white bull, the sacred animal of Min (g) and (h). Priests, the queen, and a procession of priests in two rows carry standards and images of the pharaoh and his ancestors. Like his predecessor, Ramses II, Ramses III watches the priests allow four birds to fly to the four corners of the earth to carry the royal tidings. Also, he cuts a sheaf of wheat with his sickle in the presence of priests and his queen (i), and he offers incense to Min (j). The scenes from the Festival of Ptah-Sokaris to the left of the court are depicted in the upper registers.

There are some interesting war reliefs, which start at the inner wall of the second pylon (k). The first scene shows Ramses III attacking the Libyans with his charioteers. He shoots arrows with his bow and the infantry flee in all directions. The mercenaries are in the lower row. The second scene shows him returning from battle with three rows of fettered Libyans tied before him, and two fan-bearers behind. The third shows him leading his prisoners of war to Amon and Mut.

In the corner (1) Ramses turns in his chariot to receive four rows of prisoners of war from noblemen; among them are his own sons. Hands and phalluses of the slain are counted. On the lower reaches of the rear walls of the terrace (m) and (n) are rows of royal princes and princesses.

![]() |

| Temple of Ramses III |

The Great Hypostyle Hall follows. The roof was originally supported by twenty-four columns in four rows of six, with the double row' of central columns thicker than the others. The wall reliefs show Ramses in the presence of the various deities. Adjoining each side of the hall are a series of chambers. Those to the left (o) to (r), stored valuable jewels, musical instruments, costly vessels and precious metals, including gold.

There are two small hypostyle halls (C) and (D), to the rear, each supported by eight columns, leading to the sanctuary (E). In the second of the hypostyle halls (D) there are granite dyads, or statues of Ramses II with a deity; he is shown seated with the ibis-headed Thoth, to the right, and with Maat, goddess of Truth, to the left.

On the outside of the temple there are important historical reliefs that commemorate the wars of Ramses III. Those to the rear of the temple (t) show the pharaoh’s battle against the Nubians: the actual battle scene is shown, also the triumphal procession with captives, and the presentation to Amon. On the northern wall (u) are ten scenes from the wars against the Libyans, and the naval victory over the ‘People of the Sea’. The latter is an extremely animated representation: Ramses alights from his chariot and shoots at the hostile fleet. One enemy ship has capsized, and the Egyptian vessels (distinguishable by a lion’s head on the prow) are steered by men with large oars, while the rest of the crew row from benches. Bound captives are inside the hold.

The northern wall, at (v) has scenes from the Syrian wars, which include the storming of a fortress, and the presentation of prisoners to Amon and Khonsu. On the back of the first pylon (w) is a hunt for deer, bulls and asses in the marshes. On the southern wall, at (x) is a Festival Calendar that includes a list of appointed sacrifices, as dating from the accession of Ramses III to the throne.